Not an allegory

Being the diehard Narnian fans we are, we all know that "Narnia is not an allegory, it's a supposal" (or supposition - I've seen both words used). But I've often wondered about this. Is it just a question of definition?

In a way the answer is "of course". Defining something as fitting into a certain category always depends on your definition of that category (and definitions of categories are almost always in some way ambiguous and subjective - something you learn early on if you study any semantics). But at the same time, I think for the most part most people would agree about the main elements of what makes something count, or not count, as allegory.

Right at the outset of The Silver Chair, we get a few passages which look like something dangerously close to allegory. Passages like these give me the niggling feeling that perhaps Lewis wasn't so anti-allegory when he wrote The Chronicles as he was later on in life (something I've suspected came from Tolkien's outspoken dislike of it).

In most of the Chronicles, Aslan only appears later in the story (sometimes only really at the end) and it is there that his role as the Christ-figure in the story is most clearly seen. But in The Silver Chair, Lewis is less "subtle" as we see the Lion interacting with Jill and revealing his nature right at the start.

In the conversations between Jill and Aslan in chapter two, Lewis uses what seem to me unveiled references to Christian truths (sometimes in language almost taken straight from scripture.) If allegory is an everyday story/account of events which is used to represent something unseen (or in the religious sense, spiritual), what do we make of these passages?

The first of these scenes is the most obvious - the conversation at the river where Jill wants to drink but is afraid of the lion standing there (whom, I had forgotten this until I started reading again, she does not know is the same Aslan Eustace had told her about - she has no idea that Aslan is a lion). He invites her more than once, "if you are thirsty, come and drink". When he does not move away on her asking him to and she suggests finding another stream, he says "there is no other stream". When she finally plucks up the courage (or lets her thirst overcome her fear), the water is described as "the coldest, most refreshing water ever tasted. You didn't need to drink much of it for it quenched your thirst at once."

The biblical references alluded to here can, I think, not be missed by anyone familiar with the passages in the bible where Jesus refers to himself as being or providing Living Water, and as being the "only one".

Jesus replied, “If you only knew the gift God has for you and who you are speaking to, you would ask me, and I would give you living water... Anyone who drinks this water will soon become thirsty again. But those who drink the water I give will never be thirsty again. It becomes a fresh, bubbling spring within them, giving them eternal life.” (John 4:10, 13-14)

On the last day...Jesus stood and cried out, saying, “If anyone thirsts, let him come to Me and drink. He who believes in Me, as the Scripture has said, out of his heart will flow rivers of living water.” (John 7:37-38)

Jesus said to him, “I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through Me. (John 14:6)

The next section which presents a strong, unveiled biblical parallel is when Jill suggests that Aslan has the wrong girl because he did not call them, but they asked him to let them into Narnia. His reply, "You would not have called to me unless I had been calling you," reminds me a lot of Jesus' words to the disciples: "You did not choose Me, but I chose you and appointed you that you should go and bear fruit, and that your fruit should remain..." (John 15:16a). Without getting into any controversial topics, I think we all agree that the point made here, that it was Aslan who called the children to Narnia to fulfil a certain task, as Jesus chose the disciples to be given the task of proclaiming his message and founding the church, and as we are called to fulfil certain tasks in our lives, is a good and solid Christian one.

Finally, the passage where Jill is reminded to recite the signs regularly and daily lest she forget them, ("say them to yourself when you wake in the morning, and when you lie down at night and when you wake in the middle of the night") reminds me strongly of God's command to the Israelites concerning the law:

And these words which I command you today shall be in your heart. You shall teach them diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, when you walk by the way, when you lie down, and when you rise up. (Duet 6:6-7)

There are lots of small and large lessons in The Chronicles that are much subtler than these. Sometimes it's hard to tell whether Lewis intended them or not. But I think in the case of these passages, the intention is unmistakable.

Does this mean that The Chronicles do, in fact, have allegorical aspects to them (even if they are not full allegories of the kind like Pilgrim's Progress)? Well again, that depends on your definition, but I think there is something in these that argue for Lewis' denial of allegory, or at least the bad kind of allegory.

Allegory, in the "bad sense" is something to be avoided, because of its obvious method of forcing one image onto another. It has its uses, but they are limited, as they have the tendency to annoy the reader, who spends so much time worrying about what everything means that they miss the story (that's my experience anyway).

Tolkien says something interesting about the difference between intentional and subconscious allegory in the prologue to the second edition of The Silmarillion:

I dislike allegory - conscious and intentional allegory - yet any attempt to explain the purport of myth or fairytale must use allegorical language. (And, of course, the more life a story has, the more susceptible to allegorical interpretations: while the better a deliberate allegory is made, the more nearly it will be acceptable just as story.)

So Tolkien says there's nothing wrong with a story being susceptible to allegory - so long as it is not overtly so. Yet is not what Lewis has done in these particular passages intentional allegory? I would say yes, but there is something about the way Lewis does it that saves it from the danger of it being the annoying or bad kind of allegory. Lewis is subtle.

I've said all along that these passages stuck out to me as pointing to very clear biblical references. But that is because I have read The Silver Chair a number of times, discussed it for many years, and am very familiar with the biblical truths and passages they reflect. Although I can't judge for certain, I suspect that someone unaware of the biblical passages, or reading SC for the first time and not looking for significance (which was probably the case the first time I read it, though I cannot remember), could gloss over the connections completely, and not see any kind of spiritual lesson being shoved down your throat. At least I hope and imagine that that is the case. I know Pauline Baynes was said to have illustrated LWW without being at all aware of the fact that Aslan represented Jesus (which, though it seems strange to me, is a testimony of Lewis' subtlety).

I'm not sure if this is what Tolkien meant when he said well written intentional allegory is at risk of being taken as just a story or whether he sees that as a good or bad thing. But it seems to me that Lewis gets something of both worlds. The events containing intentional allegory or spiritual lessons in this chapter are clear for those who want to see them and know how to recognise them, but appear as just a story for those who cannot. And yet I think they are more than just a story even then. They are imparting truths about life to all readers, whether as an overt Christian message or as subtle truths. I think all readers would still find beauty in the image of Aslan testing Jill's trust, of his omnipotence in being the one who called them and his insistence she not allow herself to forget the signs.

As Christians we see these passages as speaking of Christ, the only source of living water, of pointing out that he is the one who calls us to fulfil what he has planned for our lives and of the fact we must continually remind ourselves of what we believe, lest we forget in the chaos of the world (the reason we observe communion as a reminder of Christ's death).

And so, whether or not you think the word "allegory" be applied to what Lewis has done here, I think it is safe to say that he has got it right. He has got the right combination and balance of lessons with subtlety. And that is what is important.

------------------------------------

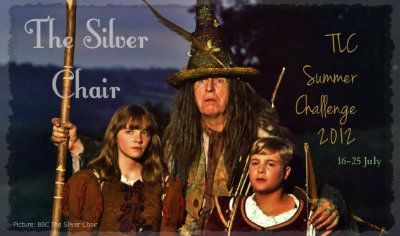

TLC Summer Challenge - 2012

TLC Summer Challenge - 2012

From 16 to 25 July we held a Summer Reading Challenge on The Lion's Call, the Chronicles of Narnia fansite which I'm a member of. The challenge was to read The Silver Chair

during that period, two chapters a day, and to write/design reflections

or something artistic inspired by those chapters. Since this blog has

been feeling a little neglected of late, I thought I'd use the

opportunity to share my reflections on The Silver Chair on it.

No comments:

Post a Comment